JANUARY 2022 NEWSLETTER

In this newsletter, John Hamilton reflects on the fog of an orphan war and the power of collateral effects.

“There’s an old saying that victory has a hundred fathers and defeat is an orphan.”

President John F. Kennedy, April 1961

Universally we admire the World War II generation for vanquishing the world of Nazi and Fascist tyranny. Not only do we hold them up as heroes who laid down their lives for each other and human freedom, we celebrate their clean victory in what the late author Studs Terkel called "the good war." We take confidence and inspiration from their win, a victory that actually has millions of fathers, my Dad and President Kennedy included.

Last September, as the Taliban resumed control over Afghanistan after our nation's longest war, I had a memorable conversation with my neighbor, Don. He is a widower and a Vietnam Veteran. I enjoy our conversations immensely. When I travel for work, Don is a good neighbor and friend. He calls me if there is a package on my doorstep or something seems out of place. He and the neighbors in my little space of the world keep an eye on things and reach out if anything seems disorderly. I think Don likes to hear a story or two about my Army buddies and the things we've done. He's invited me to go do some shooting at the range, where he's the safety officer. That's his only commitment now, once a week.

The month Kabul fell, I saw a video of an abandoned UH-60 Blackhawk that appeared to be flown on a short-lived Taliban joyride. I'm an Aviator, so this clip struck me as particularly obscene. In many ways, my job in war was cake; my friends and I flew above the fray. Down below, our nation's bravest walked and fought on the trails, plains, and ridges, protected by their armor, prowess, and friends. They didn't have the amazing ability by sleight of hand to propel themselves out of harm's way, secure in the whirring whine of metal, rotors, and burning jet fuel. Those on the ground, like my Dad in the good war, had to face the enemy out of the third dimension, eye to eye.

Even still, I know Aviators, including close friends, who have risked it all to help those down below. I've seen and heard them get shot up; I've seen the nicks to fuselage and face after the fray reaches skyward. I've seen them fly their disabled chariots off the battlefield, sometimes just to deny the enemy a moral victory of capturing a United States combat aircraft. Think about that - such bravery - simply to protect the prestige of our nation. That's a righteous pride in our ideas, our people, and the words "UNITED STATES ARMY," emblazoned across an olive drab tail boom. It's difficult to fathom, but it's true. I know many, given the legal leeway of orders, who would have risked their lives again to deny the enemy access to that Blackhawk.

Talking to Don this past September, I realized how our Vietnam service members must have felt when Saigon fell. I had just read Facebook posts from people I grew up with, people who'd never served a day in uniform, who proclaimed such a waste of treasure and lives in Afghanistan. In one case, a high school acquaintance specifically talked about a "loser" who'd wasted his life there (he wasn't referring to me, but I sure couldn't help but notice this slam on a fellow veteran). As I talked to Don, I realized we are much more alike than different, an Old Soldier and a soon-to-be Old Soldier. Just like the greatest generation, we had served admirably, but as history would have it, we had both fought in orphan wars.

Often attributed to Churchill (and at times Herman Goring, and even Robespierre) - "history is written by the victors." If so, what agency is left for the veteran of an "unvictorious" war? Such a question depends on perspective. Several days before Christmas, I struck up a conversation with a guy I encountered on a bus. He told me he had served with the Canadian Army in Afghanistan and was assigned to the same ground unit my friends and I supported with our Army Apaches. Upon learning this, I said from the bottom of my heart, "I am so sorry." He immediately knew the matter. Sadly, tragically, members of his unit had died in a horrible fratricide event when an American fighter jet dropped a bomb on them. Our Canadian friends came to help us, and for whatever wrong reason, some among us hurt them. I heard and felt the 500-pound bomb that took our friends' lives. It rattled my tent. And for those of us who study history, it should forever rattle our souls.

Then he said something I'll remember the rest of my days; something I can't write, so explicit was the language, that the fratricide incident was as screwed up as the whole twenty-year war. Nothing is as sad as an orphan longing for a lost parent, save perhaps a soldier grieving colleagues lost at the hands of a mistake. Defeat is indeed an orphan. I respect and appreciate his hard-earned right to say what he sees, and I grieve the event, but as to the entirety of the war, I see something different, and I see it often in what we do with veterans and students.

The 9:57 Project gives veterans an opportunity to process post-service life and the entirety of the war on their own terms, with personal victories separate from the actual or perceived strategic failures of the War on Terror. I firmly believe there is so much goodness available in such an approach. We've seen the transformative spirit that takes hold when service members share the beautiful things we've learned about the human condition, things realized only with a battlefield as tutor. These stories complement our overarching United 93 flagship story, the true tale of truly courageous people who foiled a surprise aerial attack on our nation's capital. We gather the veterans and students, tell the stories, and see changed lives. And then sometimes we see the collateral effect.

On Christmas Eve, I was at my Mom's in Fort Payne, Alabama. As we visited with her neighbor Jo Ann, we talked about her son Danny Foxworthy. I've never met him, but Danny feels like a brother. He was a Blackhawk crewchief in the United States Army. Jo Ann told us about a time he was involved in an event at a ground checkpoint. A vehicle approached his position. Danny instructed the driver to leave the area, and he complied. The vehicle moved a short distance down the road, then exploded in a cataclysmic IED detonation. This happened on the same day Jo Ann was in church praying for Danny's safety. I marveled at the story and remembered again the astonishing way I am familiar with Danny's combat experience- not through his Mom, but because one of my best pals, Jon Webb, was in Danny's unit. Sergeant Jonathan Webb was on the first 9:57 Project field trip to the Flight 93 Memorial in Pennsylvania. It's in no small part because of Jon's friendship, influence, and counsel that the 9:57 Project is a thing, and that you are reading this article. Jon had insight into the nonprofit world. He formed one in response to the trauma and experiences of his war. He was moved to help children in Iraq and named his effort “Orphans of War.”

I had to leave Mom and Jo Ann to finish some last-minute Christmas shopping. As I walked in downtown Fort Payne, my phone rang. It was an old friend from DC, Steve Fogelman, who called to ask if I knew anyone at Dulles Airport who could help a recently arrived Afghan woman in finding a job. The young lady, armed with a college degree and four languages, had worked at the Kabul airport. He and his wife Cindy are involved in an effort to assist those we delivered from the Taliban in the last days of the war. I knew exactly who to contact. Given the enthusiasm and Christmas spirit of Steve's phone call, I knew I should reach out sooner rather than later.

In November, the 9:57 Project had flown from Dulles to the National Flight 93 Memorial on private charters provided by Southern Airways. Not only was Southern CEO Stan Little so generous in offering these flights, he suggested a Dulles disembarkation point, noting everyone recently liberated from the Taliban by our Air Force came through the area at the airport where Southern happens to have its gate. We also never forget that Dulles was where American Flight 77 departed on September 11th. History seems to have bookends or at least seams where one book ends, and another begins. I figured perhaps Southern could take a look at this woman's credentials and give her an opportunity.

What came next was one of my best memories of my Christmas 2021, except for the look on my daughter's face as she opened gifts and special time with loved ones. I told Steve as soon as we got off the phone, I would text Stan to see if he could help in the job hunt (of course, he would immediately offer to do so). But first, Steve and I continued to discuss what helping our liberated Allies would mean as they settled down in this country and how the woman of Afghanistan, for a time, had been shown a new way. The war may have seemed like chaos, and it sure as hell was in the last days, but at the same time, in its conduct, the gifts of freedom visited the oppressed.

Over a decade ago, I walked into a bookstore and saw a young Afghan woman on the cover of Time magazine. The woman didn't have a nose; the Taliban had left her with only a hole above her mouth. For a time, Americans, in securing our own safety, were able to stave off such atrocities. In war, we asked for help from our friends. In doing so, we demonstrated what we believed about freedom and the dignity of man and woman, and we made promises about what could be. But trouble came, in the fog of the orphan war, we not only bombed our allies, to those to whom we offered hope, we upped and left.

But on this Christmas Eve 2021, as I stood on a street in Fort Payne, Alabama, I knew the entire story wasn't over, at least not yet. We didn't abandon this woman. This time, Steve, Stan, and I could say we helped at least this family claim a small victory. Despite America's battlefield retreat, I can still say about the American serviceman, as General Mattis says about his beloved Marines, that "there is no better friend, no worse enemy." We still do what we can. We help our friends. And as for our enemies, I know an Apache pilot from down the road in Prattville, who would still fly into hell, even on Christmas Eve, to defend the words “UNITED STATES,” so dear does he love the values they represent.

The post 9/11 veterans are a great generation in their own right. We are not victors that can claim 2-0 in World Wars as I’ve seen on a ridiculous t-shirt promotion. I think our true victories are yet to come. We've only begun to strive for this nation's heart and soul by showing America's young people what we've learned.

By the way, our Afghan friend did not take the offer from Southern Airways, she found a higher offer in this free market. What a very American thing to do, if you ask me. Oh, and my pals Steve and Cindy Fogleman in DC? They were the ones who introduced me to Jon Webb. Jon flew and fought with Danny, whose Mom is my Mom's neighbor, and on and on. Collateral effect. So much goodness lies ahead if we just keep an eye out for it.

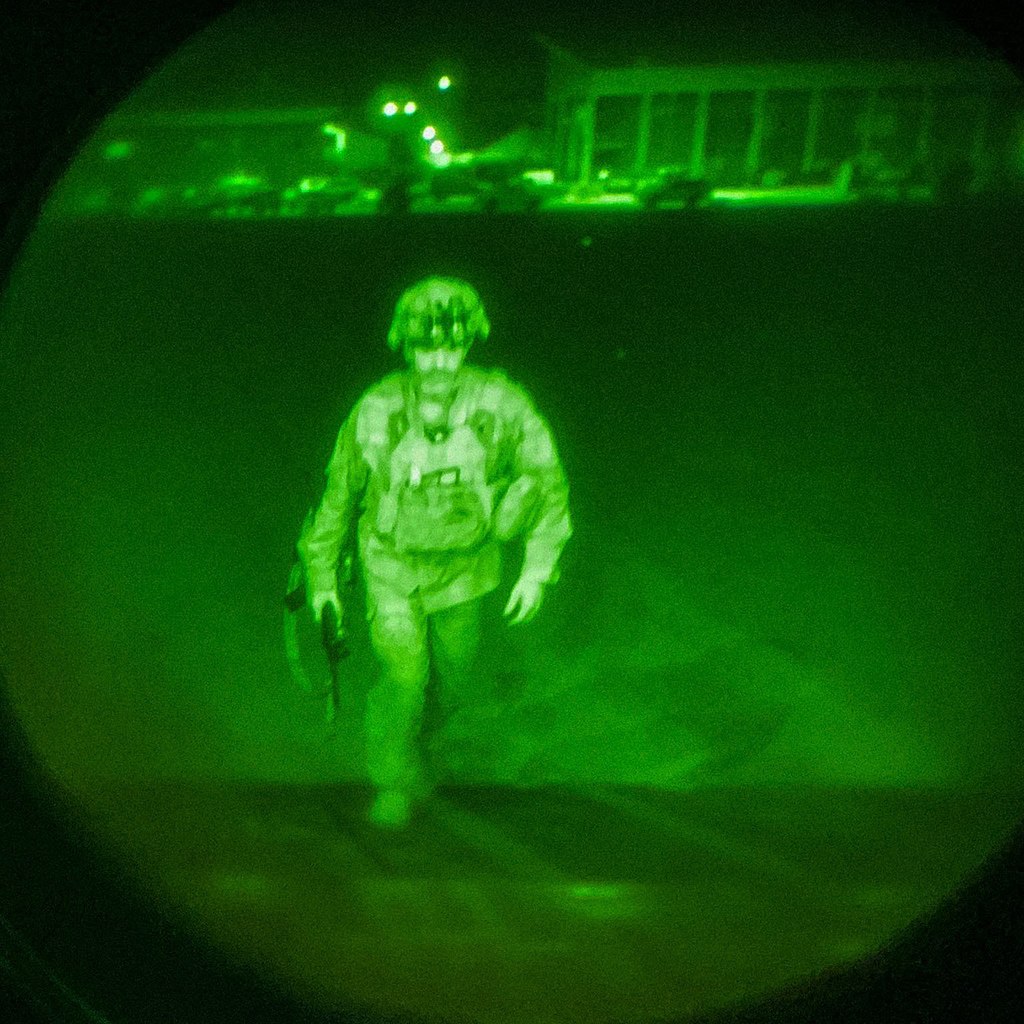

Cover image: Army Major General Chris Donahue, commander of the 82nd Airborne, steps on board a C-17 transport plane as the last U.S. service member to leave Hamid Karzai International Airport in Kabul, Afghanistan

“There’s an old saying that victory has a hundred fathers and defeat is an orphan.”

President John F. Kennedy, April 1961

Universally we admire the World War II generation for vanquishing the world of Nazi and Fascist tyranny. Not only do we hold them up as heroes who laid down their lives for each other and human freedom, we celebrate their clean victory in what the late author Studs Terkel called "the good war." We take confidence and inspiration from their win, a victory that actually has millions of fathers, my Dad and President Kennedy included.

Last September, as the Taliban resumed control over Afghanistan after our nation's longest war, I had a memorable conversation with my neighbor, Don. He is a widower and a Vietnam Veteran. I enjoy our conversations immensely. When I travel for work, Don is a good neighbor and friend. He calls me if there is a package on my doorstep or something seems out of place. He and the neighbors in my little space of the world keep an eye on things and reach out if anything seems disorderly. I think Don likes to hear a story or two about my Army buddies and the things we've done. He's invited me to go do some shooting at the range, where he's the safety officer. That's his only commitment now, once a week.

The month Kabul fell, I saw a video of an abandoned UH-60 Blackhawk that appeared to be flown on a short-lived Taliban joyride. I'm an Aviator, so this clip struck me as particularly obscene. In many ways, my job in war was cake; my friends and I flew above the fray. Down below, our nation's bravest walked and fought on the trails, plains, and ridges, protected by their armor, prowess, and friends. They didn't have the amazing ability by sleight of hand to propel themselves out of harm's way, secure in the whirring whine of metal, rotors, and burning jet fuel. Those on the ground, like my Dad in the good war, had to face the enemy out of the third dimension, eye to eye.

Even still, I know Aviators, including close friends, who have risked it all to help those down below. I've seen and heard them get shot up; I've seen the nicks to fuselage and face after the fray reaches skyward. I've seen them fly their disabled chariots off the battlefield, sometimes just to deny the enemy a moral victory of capturing a United States combat aircraft. Think about that - such bravery - simply to protect the prestige of our nation. That's a righteous pride in our ideas, our people, and the words "UNITED STATES ARMY," emblazoned across an olive drab tail boom. It's difficult to fathom, but it's true. I know many, given the legal leeway of orders, who would have risked their lives again to deny the enemy access to that Blackhawk.

Talking to Don this past September, I realized how our Vietnam service members must have felt when Saigon fell. I had just read Facebook posts from people I grew up with, people who'd never served a day in uniform, who proclaimed such a waste of treasure and lives in Afghanistan. In one case, a high school acquaintance specifically talked about a "loser" who'd wasted his life there (he wasn't referring to me, but I sure couldn't help but notice this slam on a fellow veteran). As I talked to Don, I realized we are much more alike than different, an Old Soldier and a soon-to-be Old Soldier. Just like the greatest generation, we had served admirably, but as history would have it, we had both fought in orphan wars.

Often attributed to Churchill (and at times Herman Goring, and even Robespierre) - "history is written by the victors." If so, what agency is left for the veteran of an "unvictorious" war? Such a question depends on perspective. Several days before Christmas, I struck up a conversation with a guy I encountered on a bus. He told me he had served with the Canadian Army in Afghanistan and was assigned to the same ground unit my friends and I supported with our Army Apaches. Upon learning this, I said from the bottom of my heart, "I am so sorry." He immediately knew the matter. Sadly, tragically, members of his unit had died in a horrible fratricide event when an American fighter jet dropped a bomb on them. Our Canadian friends came to help us, and for whatever wrong reason, some among us hurt them. I heard and felt the 500-pound bomb that took our friends' lives. It rattled my tent. And for those of us who study history, it should forever rattle our souls.

Then he said something I'll remember the rest of my days; something I can't write, so explicit was the language, that the fratricide incident was as screwed up as the whole twenty-year war. Nothing is as sad as an orphan longing for a lost parent, save perhaps a soldier grieving colleagues lost at the hands of a mistake. Defeat is indeed an orphan. I respect and appreciate his hard-earned right to say what he sees, and I grieve the event, but as to the entirety of the war, I see something different, and I see it often in what we do with veterans and students.

The 9:57 Project gives veterans an opportunity to process post-service life and the entirety of the war on their own terms, with personal victories separate from the actual or perceived strategic failures of the War on Terror. I firmly believe there is so much goodness available in such an approach. We've seen the transformative spirit that takes hold when service members share the beautiful things we've learned about the human condition, things realized only with a battlefield as tutor. These stories complement our overarching United 93 flagship story, the true tale of truly courageous people who foiled a surprise aerial attack on our nation's capital. We gather the veterans and students, tell the stories, and see changed lives. And then sometimes we see the collateral effect.

On Christmas Eve, I was at my Mom's in Fort Payne, Alabama. As we visited with her neighbor Jo Ann, we talked about her son Danny Foxworthy. I've never met him, but Danny feels like a brother. He was a Blackhawk crewchief in the United States Army. Jo Ann told us about a time he was involved in an event at a ground checkpoint. A vehicle approached his position. Danny instructed the driver to leave the area, and he complied. The vehicle moved a short distance down the road, then exploded in a cataclysmic IED detonation. This happened on the same day Jo Ann was in church praying for Danny's safety. I marveled at the story and remembered again the astonishing way I am familiar with Danny's combat experience- not through his Mom, but because one of my best pals, Jon Webb, was in Danny's unit. Sergeant Jonathan Webb was on the first 9:57 Project field trip to the Flight 93 Memorial in Pennsylvania. It's in no small part because of Jon's friendship, influence, and counsel that the 9:57 Project is a thing, and that you are reading this article. Jon had insight into the nonprofit world. He formed one in response to the trauma and experiences of his war. He was moved to help children in Iraq and named his effort “Orphans of War.”

I had to leave Mom and Jo Ann to finish some last-minute Christmas shopping. As I walked in downtown Fort Payne, my phone rang. It was an old friend from DC, Steve Fogelman, who called to ask if I knew anyone at Dulles Airport who could help a recently arrived Afghan woman in finding a job. The young lady, armed with a college degree and four languages, had worked at the Kabul airport. He and his wife Cindy are involved in an effort to assist those we delivered from the Taliban in the last days of the war. I knew exactly who to contact. Given the enthusiasm and Christmas spirit of Steve's phone call, I knew I should reach out sooner rather than later.

In November, the 9:57 Project had flown from Dulles to the National Flight 93 Memorial on private charters provided by Southern Airways. Not only was Southern CEO Stan Little so generous in offering these flights, he suggested a Dulles disembarkation point, noting everyone recently liberated from the Taliban by our Air Force came through the area at the airport where Southern happens to have its gate. We also never forget that Dulles was where American Flight 77 departed on September 11th. History seems to have bookends or at least seams where one book ends, and another begins. I figured perhaps Southern could take a look at this woman's credentials and give her an opportunity.

What came next was one of my best memories of my Christmas 2021, except for the look on my daughter's face as she opened gifts and special time with loved ones. I told Steve as soon as we got off the phone, I would text Stan to see if he could help in the job hunt (of course, he would immediately offer to do so). But first, Steve and I continued to discuss what helping our liberated Allies would mean as they settled down in this country and how the woman of Afghanistan, for a time, had been shown a new way. The war may have seemed like chaos, and it sure as hell was in the last days, but at the same time, in its conduct, the gifts of freedom visited the oppressed.

Over a decade ago, I walked into a bookstore and saw a young Afghan woman on the cover of Time magazine. The woman didn't have a nose; the Taliban had left her with only a hole above her mouth. For a time, Americans, in securing our own safety, were able to stave off such atrocities. In war, we asked for help from our friends. In doing so, we demonstrated what we believed about freedom and the dignity of man and woman, and we made promises about what could be. But trouble came, in the fog of the orphan war, we not only bombed our allies, to those to whom we offered hope, we upped and left.

But on this Christmas Eve 2021, as I stood on a street in Fort Payne, Alabama, I knew the entire story wasn't over, at least not yet. We didn't abandon this woman. This time, Steve, Stan, and I could say we helped at least this family claim a small victory. Despite America's battlefield retreat, I can still say about the American serviceman, as General Mattis says about his beloved Marines, that "there is no better friend, no worse enemy." We still do what we can. We help our friends. And as for our enemies, I know an Apache pilot from down the road in Prattville, who would still fly into hell, even on Christmas Eve, to defend the words “UNITED STATES,” so dear does he love the values they represent.

The post 9/11 veterans are a great generation in their own right. We are not victors that can claim 2-0 in World Wars as I’ve seen on a ridiculous t-shirt promotion. I think our true victories are yet to come. We've only begun to strive for this nation's heart and soul by showing America's young people what we've learned.

By the way, our Afghan friend did not take the offer from Southern Airways, she found a higher offer in this free market. What a very American thing to do, if you ask me. Oh, and my pals Steve and Cindy Fogleman in DC? They were the ones who introduced me to Jon Webb. Jon flew and fought with Danny, whose Mom is my Mom's neighbor, and on and on. Collateral effect. So much goodness lies ahead if we just keep an eye out for it.

Cover image: Army Major General Chris Donahue, commander of the 82nd Airborne, steps on board a C-17 transport plane as the last U.S. service member to leave Hamid Karzai International Airport in Kabul, Afghanistan