OCTOBER 2022

When Sergeant Alvin C. York registered for the draft in 1917, he could not have possibly known what was in store for him. Initially denied status as a conscientious objector, York would eventually lead one of the most daring missions in American military history when, in the fall of 1918, he and a small number of the 82nd "All American" Airborne Division captured 132 Germans in a machine gun nest in the Argonne Forest. This courageous endeavor earned him the Medal of Honor, a rare set of high honors in both Italy and France, and his exploits were the subject of the highest-grossing film of 1941, entitled Sergeant York.

Following World War I, York’s transition back into civilian life was marked by continued service, albeit in a different form, as the citizen-turned-soldier-turned-citizen served as a founding member of the American Legion and as a staunch advocate for the funding of a new road to service the rural area in which he was raised, a highway that is now U.S. Route 127 running through the Cumberland Plateau near Jamestown, Tennessee. Indeed, his service to the nation did not end when the war was over; in some ways, it was merely the beginning.

Like York, American veterans today continue to serve their communities in novel ways. Yet what is different for veterans of the 21st century is the historical context within which they are making their re-entry, a context that makes it far more difficult than it once was. The challenges associated with veterans returning from war today have led to a deepening of the phenomenon known as the civil-military divide. It is defined by a growing chasm between the armed forces and the civilian world and can be seen in a myriad of ways: Americans are less and less likely to have an immediate family member in the military, military bases are increasingly located in military-friendly southern states making exposure in other geographic areas more and more sparse, and veterans are more likely to feel a sense of alienation when returning home than they have in the past.

In 1918, for example, the U.S. mobilized 4 million American men to serve in the war, about 4% of the total population at the time. Today, less than 1% of Americans currently serve in the military. The military in 1918 was based on selective service, but today’s military is an all-volunteer force. Moreover, efforts on the homefront were taken up by millions of American citizens during World War I, and soldiers who returned home were victorious members of the “Great War,” a conflict that was dubbed by many to be the “war to end all wars.”

There are a variety of ways to combat the civil-military divide today, and while it was not our express purpose when we began to bring veterans and schools together, we at The 9:57 Project are working to narrow the divide one classroom at a time. Although not a veteran myself, I have seen firsthand how providing veterans with a space to share the virtues of civic responsibility with young people creates a healing experience for our service men and women. Moreover, connecting veterans with young people helps strengthen the present and future of American democracy because of the disposition that our veterans have towards service. Research indicates that veterans are more likely to vote than their non-veteran counterparts, more likely to own their own business than non-veterans, and more likely to be a member of a civic organization than non-veterans. Further, they are more likely to be employed and earn more money than those who have not served in the armed forces. This is a group of people who are still very civically engaged even though their enlistments are up, and therefore provide ideal role models for young people.

And what better civic space to share the lessons they've learned than within a school? Like the military, schools are institutions that work to defend the foundations of our society in the never-ending struggle for a healthy, resilient democracy. We must continue to support efforts to amplify this natural partnership.

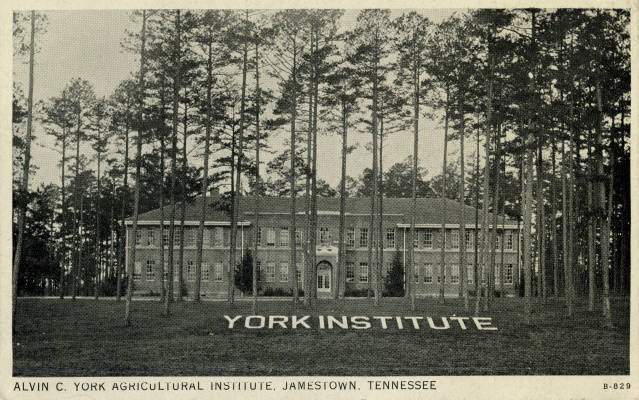

When I first read of Sergeant York's humble efforts to continue to serve following World War I, I was impressed but not surprised. He was a veteran, after all, and a service-first mindset was to be expected. But it was heartening to learn specifically of his civic efforts in the area of education. When he was asked about what he wanted to do upon his return following the war, he answered that he planned to do two things: marry his childhood sweetheart Gracie and build a school. And sure enough, he accomplished both missions. Following his marriage, the York Institute was founded in 1926 and was led by York himself for years. He even handed out diplomas to students every year at graduation for decades following the school's founding.

The institution still stands today and is a reminder of the enduring power of the role that schools can play in narrowing the civil-military divide, and what the commitment of just one veteran can mean for strengthening American civic life.

Learn more about Sergeant York here, here, and here.

Peter Findler

Cover image: The York Institute in Fentress County, Tennessee. Founded in 1926 as a private school, it was eventually transferred to the State Board of Education of Tennessee in 1937. Today, it is the only state-run comprehensive secondary school in the United States. Image credit: Tennessee Virtual Archive

Following World War I, York’s transition back into civilian life was marked by continued service, albeit in a different form, as the citizen-turned-soldier-turned-citizen served as a founding member of the American Legion and as a staunch advocate for the funding of a new road to service the rural area in which he was raised, a highway that is now U.S. Route 127 running through the Cumberland Plateau near Jamestown, Tennessee. Indeed, his service to the nation did not end when the war was over; in some ways, it was merely the beginning.

Like York, American veterans today continue to serve their communities in novel ways. Yet what is different for veterans of the 21st century is the historical context within which they are making their re-entry, a context that makes it far more difficult than it once was. The challenges associated with veterans returning from war today have led to a deepening of the phenomenon known as the civil-military divide. It is defined by a growing chasm between the armed forces and the civilian world and can be seen in a myriad of ways: Americans are less and less likely to have an immediate family member in the military, military bases are increasingly located in military-friendly southern states making exposure in other geographic areas more and more sparse, and veterans are more likely to feel a sense of alienation when returning home than they have in the past.

In 1918, for example, the U.S. mobilized 4 million American men to serve in the war, about 4% of the total population at the time. Today, less than 1% of Americans currently serve in the military. The military in 1918 was based on selective service, but today’s military is an all-volunteer force. Moreover, efforts on the homefront were taken up by millions of American citizens during World War I, and soldiers who returned home were victorious members of the “Great War,” a conflict that was dubbed by many to be the “war to end all wars.”

There are a variety of ways to combat the civil-military divide today, and while it was not our express purpose when we began to bring veterans and schools together, we at The 9:57 Project are working to narrow the divide one classroom at a time. Although not a veteran myself, I have seen firsthand how providing veterans with a space to share the virtues of civic responsibility with young people creates a healing experience for our service men and women. Moreover, connecting veterans with young people helps strengthen the present and future of American democracy because of the disposition that our veterans have towards service. Research indicates that veterans are more likely to vote than their non-veteran counterparts, more likely to own their own business than non-veterans, and more likely to be a member of a civic organization than non-veterans. Further, they are more likely to be employed and earn more money than those who have not served in the armed forces. This is a group of people who are still very civically engaged even though their enlistments are up, and therefore provide ideal role models for young people.

And what better civic space to share the lessons they've learned than within a school? Like the military, schools are institutions that work to defend the foundations of our society in the never-ending struggle for a healthy, resilient democracy. We must continue to support efforts to amplify this natural partnership.

When I first read of Sergeant York's humble efforts to continue to serve following World War I, I was impressed but not surprised. He was a veteran, after all, and a service-first mindset was to be expected. But it was heartening to learn specifically of his civic efforts in the area of education. When he was asked about what he wanted to do upon his return following the war, he answered that he planned to do two things: marry his childhood sweetheart Gracie and build a school. And sure enough, he accomplished both missions. Following his marriage, the York Institute was founded in 1926 and was led by York himself for years. He even handed out diplomas to students every year at graduation for decades following the school's founding.

The institution still stands today and is a reminder of the enduring power of the role that schools can play in narrowing the civil-military divide, and what the commitment of just one veteran can mean for strengthening American civic life.

Learn more about Sergeant York here, here, and here.

Peter Findler

Cover image: The York Institute in Fentress County, Tennessee. Founded in 1926 as a private school, it was eventually transferred to the State Board of Education of Tennessee in 1937. Today, it is the only state-run comprehensive secondary school in the United States. Image credit: Tennessee Virtual Archive