OCTOBER 2021 NEWSLETTER

How do we come to know what we know about the past? To what extent is our understanding of history the result of a collective memory that has been passed down to us? How do memory and history interact to produce an understanding of the past, present, and future? The history of September 11th, 2001, can point to a variety of avenues for investigation, from the Cold War context to the new face of war in the 21st century. But in my years as a high school history teacher and in my work with the 9:57 Project, I have found that investigations of the memory of 9/11 produce a powerful learning experience that not only introduces the history of this era but also brings people closer together in the process.

In my capacity as chair of the Social Studies department at Wakefield School in The Plains, Virginia, I asked my colleagues to consider the ways in which to engage our students in grades six through twelve concerning the 20th anniversary of September 11th, 2001. Our discussion soon settled on the compelling realization that, unlike other anniversaries in history, this particular one was special in that our students, each of them without a firsthand memory of that day, were surrounded by adults who remember it vividly. And so we quickly decided to ask our students to find those people, interview them about their experiences, and write about what happened on that fateful day through the memories of those who remember it.

I’ve read hundreds of pages of our students’ work over the past week and a half, and despite each one being unique, there is a remarkable amount of shared experience expressed throughout their work. We, those who were alive at the time, remember the bright blue sky that morning; we vividly recall the transition from believing the first plane was an accident to the realization that America was under attack; we remember the people around us, the emotions we shared, and the “flashbulb” memories of exactly where we were when we learned of what had happened. We remember the unity that swept the nation in the days and weeks following the attacks symbolized in the seemingly ubiquitous American flags, the efforts to give blood, the prayer vigils, and the simple courtesies extended to those around us as we bonded together in response to the unthinkable tragedy.

And even though none of the accounts I read describe being in New York City or at the Pentagon that day, 9/11 happened in California and Nebraska and Spain and South Korea. Even if we weren’t there, 9/11 happened to each one of us no matter where we were. Indeed, it seems to have happened everywhere. The experience is at once individual and collective in that each of us holds our own memory of the events, and the whole of those memories combined manifests a unity of experience. In fact, the act of passing on our memories to those who come after us is an expression of unity in and of itself. The most personally meaningful stories that I read were of my students’ admission that, if it weren’t for this assignment, they may never have spoken with their family about 9/11. The very act of asking about the past literally brought families together at a time when they would have otherwise been apart.

This highlights the difference between history and memory. As the historian David Blight puts it, history can be accessed by everyone while memory is passed down through the generations. History relies on training while memory relies on experience. History is interpreted while memory is owned. It is this process of memory owning and sharing that holds the power to engage young people in the study of history and, I believe, has the power to unite us as we explore our shared past.

Our work at the 9:57 Project is ultimately about bringing people together. We give veterans a space to share their memories with students, and we give students the space to ask honest questions about the history of our nation and world. I think I speak for all of us in saying that I am proud to be a part of this effort to take the worst day of the 21st century - one that could yet sow further division - and use it to bring us closer together.

Peter Findler

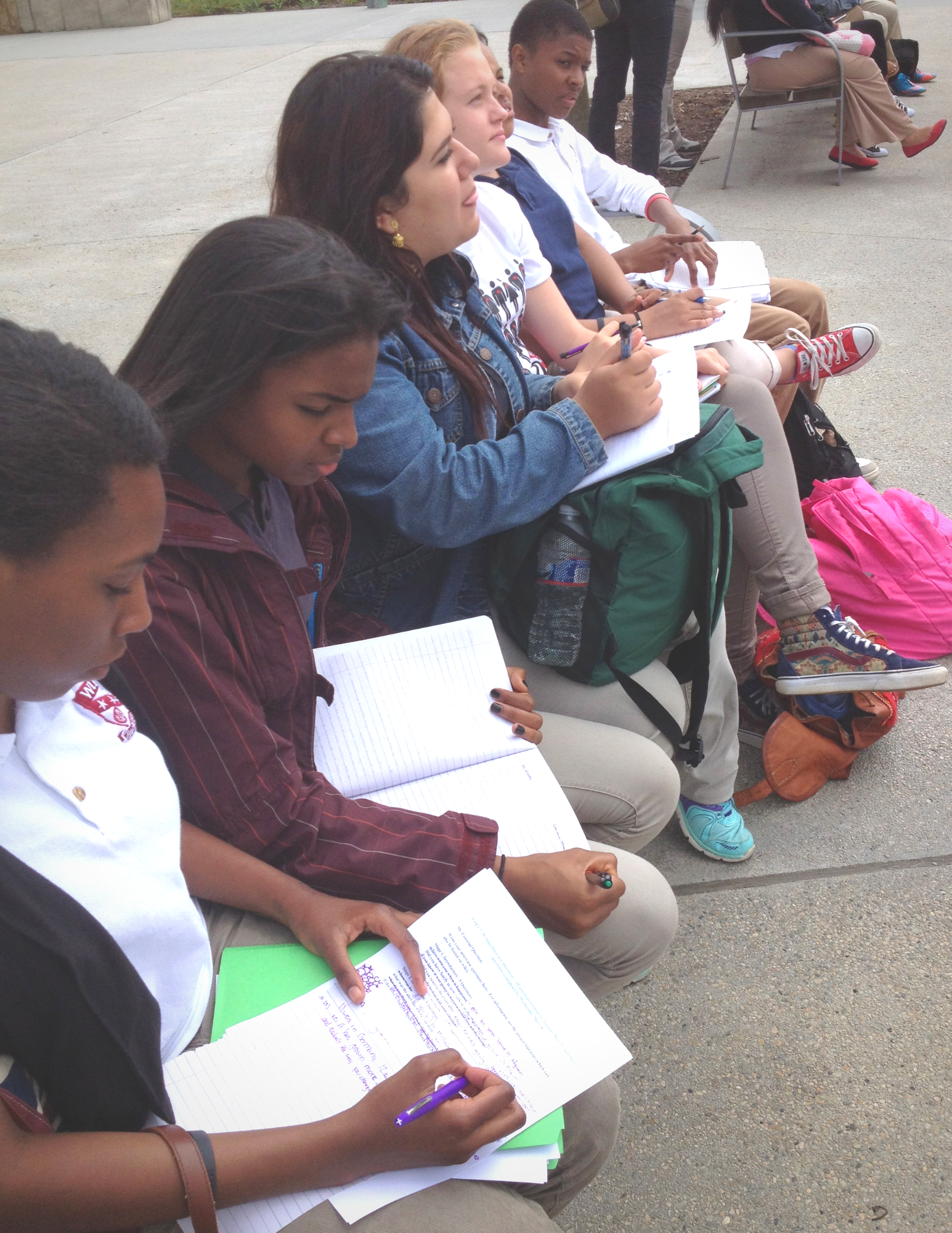

Cover image: Students conduct a group interview at the National Flight 93 Memorial

In my capacity as chair of the Social Studies department at Wakefield School in The Plains, Virginia, I asked my colleagues to consider the ways in which to engage our students in grades six through twelve concerning the 20th anniversary of September 11th, 2001. Our discussion soon settled on the compelling realization that, unlike other anniversaries in history, this particular one was special in that our students, each of them without a firsthand memory of that day, were surrounded by adults who remember it vividly. And so we quickly decided to ask our students to find those people, interview them about their experiences, and write about what happened on that fateful day through the memories of those who remember it.

I’ve read hundreds of pages of our students’ work over the past week and a half, and despite each one being unique, there is a remarkable amount of shared experience expressed throughout their work. We, those who were alive at the time, remember the bright blue sky that morning; we vividly recall the transition from believing the first plane was an accident to the realization that America was under attack; we remember the people around us, the emotions we shared, and the “flashbulb” memories of exactly where we were when we learned of what had happened. We remember the unity that swept the nation in the days and weeks following the attacks symbolized in the seemingly ubiquitous American flags, the efforts to give blood, the prayer vigils, and the simple courtesies extended to those around us as we bonded together in response to the unthinkable tragedy.

And even though none of the accounts I read describe being in New York City or at the Pentagon that day, 9/11 happened in California and Nebraska and Spain and South Korea. Even if we weren’t there, 9/11 happened to each one of us no matter where we were. Indeed, it seems to have happened everywhere. The experience is at once individual and collective in that each of us holds our own memory of the events, and the whole of those memories combined manifests a unity of experience. In fact, the act of passing on our memories to those who come after us is an expression of unity in and of itself. The most personally meaningful stories that I read were of my students’ admission that, if it weren’t for this assignment, they may never have spoken with their family about 9/11. The very act of asking about the past literally brought families together at a time when they would have otherwise been apart.

This highlights the difference between history and memory. As the historian David Blight puts it, history can be accessed by everyone while memory is passed down through the generations. History relies on training while memory relies on experience. History is interpreted while memory is owned. It is this process of memory owning and sharing that holds the power to engage young people in the study of history and, I believe, has the power to unite us as we explore our shared past.

Our work at the 9:57 Project is ultimately about bringing people together. We give veterans a space to share their memories with students, and we give students the space to ask honest questions about the history of our nation and world. I think I speak for all of us in saying that I am proud to be a part of this effort to take the worst day of the 21st century - one that could yet sow further division - and use it to bring us closer together.

Peter Findler

Cover image: Students conduct a group interview at the National Flight 93 Memorial